Vermont is a very special place, a tiny nugget nestled in New England, better known for cows than commerce.

Her gentle beauty inspires great minds to wander creatively. Because of one of them, there is a certain telescope like no other. In fact those who encounter it often do not guess, or even believe, that it is a telescope. Were it not so optically profound, it would be called sculpture, fine art, or a sundial. Some think it looks like a swan, others, Spartan armor, but there is one point of universal accord: all find it beautiful.

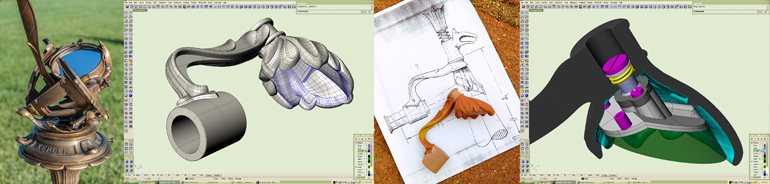

It is a reflecting telescope, that ingenious device invented by Sir Isaac Newton, all mirrors and no smoke, but it has turned the familiar design on its head. The tube is gone, replaced by a slender leaf which holds the optics.

The instrument is floral grace incarnate, more tulip than telescope. Sensuous Art Nouveau curves lighten bronze into botany, belying its robust structure. Comfortable as a sculptural garden centerpiece, it surrenders its optics in seconds, transforming to a sundial and sculpture year round, a visual anchor to a landscape.

Ninety years ago there lived in Vermont a gentleman who was most enchanted by the magic of the night sky.

His name was Russell W Porter. The father of amateur astronomy in America, the founder of the Springfield Telescope Makers, an Arctic explorer and navigator, a painter of exquisite Inuit portraits and an instructor of architecture at MIT, he was enthralled by those unanswerable questions that swirl in a thoughtful man’s mind when he contemplates the starry crunch of the Milky Way.

So captivated, in fact, that he enticed his fellow workers at Jones & Lamson, a machine tool company in Vermont where he worked in optics, to step out, look up, and marvel. To better witness the show he leveraged his immense artistic talent and created his own magic, a gift to the world in the form of a telescope so beautiful and astonishingly simple that ninety years later it still captivates imaginations and delights.

Along with his telescope Porter gave a bigger gift: the invitation to gaze upwards, contemplate the night sky, be humbled and join hands with a thousand generations which did the same, for with his instrument one reaches back in time to an age when tools married a reverence for beauty to an elegance of function. By simply aiming one small mirror, embraced by leaves of bronze, one can touch the moon, the planets, and beyond. Adults and children alike are swept to a shared moment of whispered awe when a silent, glowing moon, her rubbled craters casting long shadows, fills the field of view.

Little did Porter realize that his telescope would be a model for the design of the 200 inch Hale telescope in San Diego, which he helped create and which he drew magnificently. Nor did he anticipate that his masterpiece would find a home in the nation’s glorious attic, the Smithsonian. Or that another Vermonter of similar passions would resurrect his artistry ninety years later.

Enter a machinist and inventor who lives on a hilltop with a view to make one sigh.

His name is Fred Schleipman, and his woodpiles are perfect. They’ll outlast the pyramids, but they don’t hold a candle to the things he engineers: templates for brain surgery, bearings that spin at a million rpm, and the resurrection of the Porter Garden Telescope. Forty years ago, while photographing an eclipse in Africa, he met Bert Willard, the biographer of Russell Porter and curator of the Springfield Telescope Maker’s museum where Schleipman later visited, first saw the Garden Telescope and began to dream of resurrecting it. Little did he guess that it would take 30 years to convince a cautious organization that his skills would assure an instrument worthy of its endorsement.

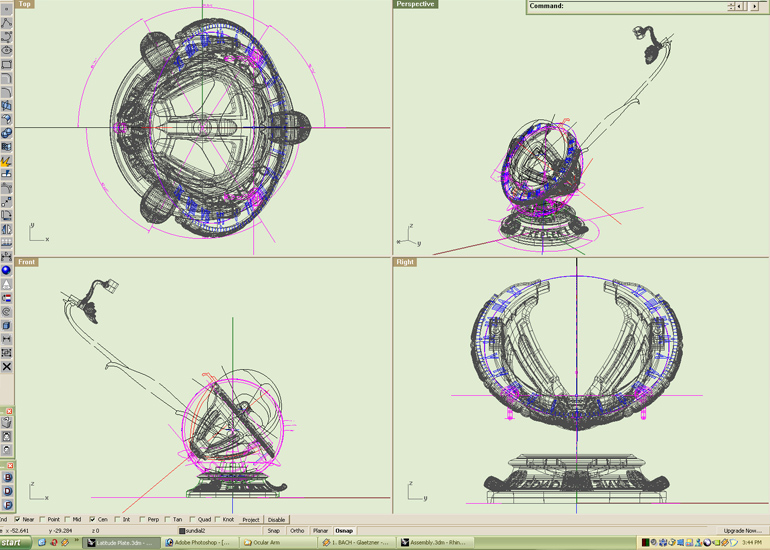

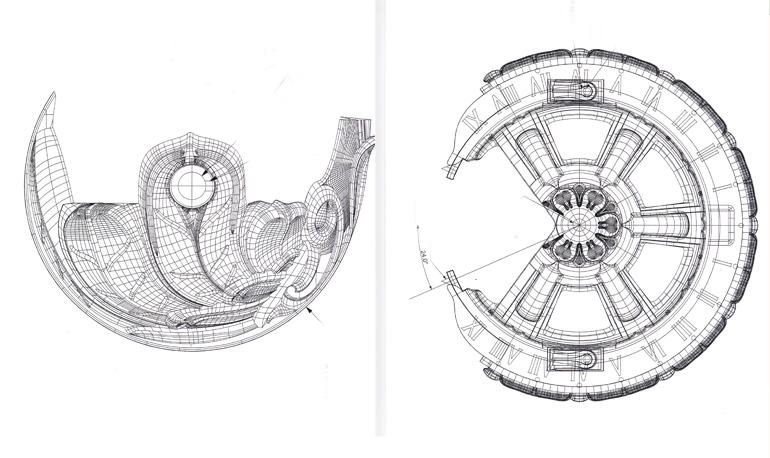

Schleipman’s crusade was dauntingly complex. As he says: “Politics preceded engineering: it took a long courtship to win trust and collaboration. Then came the hard stuff. We needed to replace lost patterns in order to cast the thirty odd components of the telescope.

Because bronze shrinks in devilishly tricky ways, those patterns must be subtly bigger than the piece they yield.

Castings, like cherry pies, look the same, but when one worries about tenths of thousandths of an inch, they are not. Not at all. They’re not like pennies at the mint, but the machining has to coax every casting to dimensional conformity, and if we’re not accurate to tenths of thousandths, the telescope won’t move with the pleasing buttery smoothness, all dry bronze on bronze, which we deliver.

And finally, but perhaps most importantly, was the question of optics. A mirror precise to millionths of an inch in its curvature and the supporting optics emerged from the wisdom of two designers of military satellite optics in Boston. Then we added the mechanism to minutely adjust those optics with a laser, allowing for a pleasingly sharp image.

We were aware from the very start that while the science was critical, we were not simply creating another telescope. Not by a long shot. We were on a mission to reintroduce a significant and historic piece of art, and our efforts have always been aimed at improving the quality, finish and beauty of every piece. The difference is in the details, so we even make our own eyepieces and turn many of the visible screws which are then knurled, given patina and buffed to simulate the burnish of decades of touch.

To that end we have been fortunate to find a superlative pattern maker in Dave Nugent of New Hampshire, in the vastly skilled machinist Norm Williams of Montana and two foundries whose work is the best we have found after years of trial and error. And our friends Bert Willard and James Daley, optical engineers at a national laboratory who design satellite optics, have given the telescope eyes which can discern the moons of Jupiter. Perhaps our workflow is not completely efficient, but there’s no room for compromise, and we do not and will not go overseas. Ever. The talent is right here.

The Garden Telescope has charmed audiences around the world.

It has stood by Bugattis and Delahayes at the Concours d’Elegance at Pebble Beach, shared space with Galileo’s world changing miracle in Philadelphia, bowed to millions on CBS Sunday Morning, and delighted the Queen in London. When British astronomer Sir Patrick Moore saw the telescope, he dubbed her “Capella”, after one of the brightest stars, always visible in the Northern hemisphere. The name is fittingly feminine and beautiful, and was bestowed, appropriately, by the man who caused a lunar crater be named for Russell Porter.

But most importantly she has whisked countless folks to the heavens on a trip they’d never taken, creating treasured memories for kids in pyjamas who bottled fireflies and went to the moon all on the same summer evening.

The world loves Vermont. Her quiet demeanor and soothing landscape invoke a nostalgia for a time before locks, when things were done with a handshake, honestly and well. Very well. The respect is well earned. We aim to keep it so.